Is AI Generated Imagery Art? If So Who Is The Artist?

- Alexander Eveleigh

- Sep 1, 2024

- 32 min read

A discussion on AI generated Imagery.

Hey everyone! So, I've got something new to share with you all. I just finished writing a dissertation on the topic of whether AI-generated imagery can be considered art and who should be credited as the artist. It's not flawless, but it's definitely an interesting subject to dive into. I tried my best to provide an unbiased, academic perspective on the matter.

I hope you find this piece of writing intriguing. Feel free to drop your thoughts in the comments, and if you have any additional insights, I'd love to hear them!

-Alex

Is AI Generated Imagery Art? If So Who Is The Artist?

Alexander Eveleigh, 02/2024

USE OF AI DISCLAIMER!

Due to the nature of this dissertation, some AI has been used in its creation in the form of AI generated quotes and AI generated Imagery as figures. All uses of AI within this dissertation have been disclosed with captions or footnotes. All other writing should be considered as my own, unless otherwise referenced.

Introduction

AI has been fantasised as a means to free humanity from the burden of the rat race. A way for the layman to be unshackled from the 9 to 5 slog and be able to truly enjoy life with time for creative self-expression, sports, and the exploration of passions. Alternative foretelling of AI has spun tales of mass destruction and human extinction at the hands of our own creations. Today’s truth is much less exciting, and more depressing than either fantastical alternate reality. Instead, the reality we find ourselves in today is a miserable limbo. AI seeks to steal the high paying, high skilled jobs lower income people have strived towards for years, all the while stealing our creativity from us. AI is not replacing the low skill, high risk, undesirable jobs as we had collectively hoped for. It is not freeing us from the office to seek greater pleasures in life. Instead, it rips opportunity from our hands, throwing us downwards into the pit of undesirable labour we so eagerly seek to escape. Turning to the weekends sweet release from the grind, our once sacred hobbies have also been corrupted by AI. Music, animation, arts, all captured in a cold digital embrace. The professional artists scramble to prepare themselves for the coming storm as creativity, human beings’ greatest asset, is commodified while the hobbyists look on in horror as their passions are outshone by the click of a button. Others view AI more favourably, hailing it as an asset, a powerful weapon in the ever-increasing battle for perfection in a world of infinite ambition and finite time. Regardless of which truth you live, all truths still leave one pertinent question left unanswered regarding AI. Is AI generated imagery art? There are multiple arguments to explore, each with valid points.

Chapter 1: What is Art?

Introduction

Defining art is a task as old as civilisation, and as yet unmastered. All attempts, by revolutionary art theorists or otherwise, have failed. Complicating the task, many disciplines could be used to answer the question. Linguists would have a different, but potentially valid way of defining art when compared to an art theorist or philosopher. Within disciplines there are multiple working definitions of art. Keeping this in mind how does one attempt to answer the question of what art is? With great difficulty. Acceptance of failure to answer the question is also acceptance of failure to understand if Ai generated imagery is art. For the purpose of academic pondering, it is pertinent instead to breakdown existing definitions of art. In doing so we can discover a definition of art that is sufficient for this discussion, or craft a unique, iterative, definition of art.

Arts merit and art institutions.

“That isn’t art, I could do that!”; a common sentiment amongst armchair art critics. An exclamation of disdain against works perceived to have taken little skill to produce. Yves Klein is one artist you would expect such criticism of. His series of blue paintings totalling into the hundreds (later given names starting with IKB followed by a number) are simplistic applications of paint onto canvas with little technical skill employed in their creation. Despite the meaning behind this body of work, described as a ‘rejection of representation in painting’ (Howarth, 2000) public commentary around the art remains unfazed. The general public’s engagement with arts, and their appreciation of them, can be condensed down into three aspects. The aesthetic of the works, the meaning behind the work and the weight of that meaning, and the perceived skill employed in the creation of the works (Freeland, 2001). Works are generally appreciated if they have high levels of either quality, however positive appreciation of a work is not often generated purely by high levels of one quality, but a complete lack of the others. In cases such as these, the work is most often dismissed out of hand as ‘not art’. This concept shall henceforth be referred to as the ‘merits’ of the work. Each individual assigns merit, and subsequently value to a piece of work as a matter of personal preference. This method of defining art is the most common. The layman does not engage with art in an academic context, nor should they be expected to. Arts’ primary purpose is for individual and cultural enrichment, not as a subject of academic inquisition. Consequentially no individual can be blamed for defining art based on personal merits.

Problems arise when the artistic elite seek to gatekeep art by forcing their personal merits onto the wider art world, commonly through the creation of the art institution. Present throughout history, two prominent examples being the academies of arts in France, and later in England. Art institutions, run by the artistic elite, wield a powerful sword used to steer and control public opinion on the definition and acceptance of art. One side of this sword is used to fight for artists deemed worthy by the artistic elite that wield it. Attaining critical acclaim from the artistic institution is often followed by a rise in popularity of the artist; increased patronage. The other, equally sharp and potent side of this sword is used to cut down the avant-garde, minorities, and undesirables from achieving prominence and recognition within the art world. In doing so the art institution creates a “virtual monopoly on public taste and official patronage” (Jason Rosenfeld, 2004).

The Paris Salon was an esteemed art show put on by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, another

prominent artistic institution responsible for dictating the definition of art in France during its time. Historically the Académie des Beaux-Arts ruled with an iron fist and strict requirements. Works were expected to have light, delicate brush stokes, warm saturated colours, and an ethereal beauty to them, as seen in Venus of Urbino.

In 1863 the Emperor of France decided that the rules dictating what could be shown at the Paris Salon were “unduly strict”, and consequently he created the Salon des Refuses (Jamot, 1927). However, the public was aligned with the opinions of the academy, and controversy arose surrounding the works shown at this exhibition. Olympia by Manet stood in stark contrast to the traditional expectations. The brush strokes are rough and heavy, colours cold and natural, with a realistic, natural representation of the scene, devoid of ethereal beauty. The flames of controversy blazing around this work were engorged by the representation of Olympia as a prostitute, a working lady, in strong and defiant contrast to the much beloved Venus of Urbino. It is this attempt to undermine the foundation of the idolised nude and academic

tradition that draws such strong flames. (712, 2024) Today Olympia is a well-regarded staple of the art world, propelled to fame by the flames of controversy but carving a place for itself in the harsh world of the art institution, and in doing so undermining the control the art institution can exert upon the definition of art. Olympia now stands as a burning example of the shortcomings of defining art based of the preferences of an artistic elite, forever calling into question the integrity of any definition proposed by said elite and the institutions they run.

In today’s world we see a much broader inclusion of works within the art institution. Movements such as modernism, post modernism, contemporary, and more, would have been laughed out of the Paris Salon as the scrawlings of a child or a maniac, but now demand high prices, respect, and recognition as art without debate or question. In contrast to institutions of the past gatekeeping art by employing strict technical and visual rules, today’s institutions fail to equitably represent art by underrepresenting minority groups (Béhague, 2006). Clear racial bias is present within the American art world with an extensive list of underrepresented groups. Alaska Natives (Inuit or Aleut), Black/African Americans, Mexican Americans/Chicanas/Chicanos, Native American Indians, Native Pacific Islanders (Polynesian/Micronesian), and Puerto Ricans have all been identified as groups whose underrepresentation has been “Severe and Longstanding (Béhague, 2006). Looking at more modern research we also see an underrepresentation of LGBTQ+ artists within the American arts world. Representation of queer artists tends to be ‘hyper sexualised or desexualised’, commodifying queer individuals as merely sexual objects, or exhibits of life with AIDS/HIV (Schuh, 2017). This narrow representation of queer individuals serves not as a platform to garner understanding and acceptance, but instead serves to strengthen the walls boxing the queer individual into harmful and offensive stereotyping, the likes of which contribute to prevailing violence and discrimination.

Through these examples the shortcomings of a merit-based method of defining art are highlighted. The quality and definition of art are in fact judged according to individual thoughts and preferences and therefore no universal definition is possible. Exploration of multiple case studies and research also shows the failings of the Institution in creating a definition of art, it serves instead as the gate keeper preventing true art from being accepted.

A linguist’s definition of arts.

Individualised definitions of art results in inconsistent classifications. Establishments historic attempts to define art are as fundamentally flawed as merit-based definition, differentiated by the artistic elite’s combined merit system. The power of these establishments allows them greater control over the art world, but ultimately, they are equally flawed. Consequently, to properly define art we must turn away from opinion to science.

Linguistics is a key science to explore when trying to define a word. The study of semantics in particular is the subsection of linguistics focusing on the definition of words. Predominantly the meaning of words is defined by the people who use them. Language is an ever-evolving entity, moving to reflect the growth of humanity and culture. (Stanislavivana, 2023) This process of words developing or adopting new meaning is called neology. (Anon, 2024) Neology is a broad term used to describe all methods in which a word or meaning of a work can be created, altered, or replaced. Modern examples of Neologisms include: google, to conduct research using the internet search platform google; and mouse, traditionally a small rodent creature, now also a human interface device used to control computers. Neology can also include the development and growth of a word to develop and expand upon its meaning, while still retaining its existing meaning. Neology requires the development of language by humanity, most commonly through the natural evolution of language. Humanity is messy and disorganized, and so too is language, evolving to take on whatever meaning, and expression assigned to it. Because of this, words meanings are driven not by any scientific categorisations, but instead by whatever humanity wishes. For example, if the entire English-speaking world woke up tomorrow and suddenly decided the word ‘apple’ no longer referred to the fruit, but instead referred to an umbrella, then an apple would be an umbrella, regardless of any logic or scientific reasoning. Art too succumbs to this issue, making it particularly difficult to define. Any reasonable or correct definition of arts could at any point become invalid by the evolution of language. The biggest example of this in today’s world regards AI generated imagery, coined by the masses as ‘AI Art’. The only thing preventing AI generated imagery from being art is the mass opposition to the categorisation. Should this opposition disappear, and ‘AI Art’ become the uncontested manner of referring to AI generated imagery, then AI generated imagery will be art, regardless of any other manner of categorisation. However, while this fight to define AI generated imagery unfolds, alternative methods of categorisation can be used to influence the definition of AI generated imagery as art or not.

(Factoid: the term ‘AI’ itself falls under this same concept, where the true categorisation of AI differs from the actual technology employed today)

(Another factoid: factoid itself is an example of a neologism, originally meaning something speculated to be fact, but unconfirmed as such, now holds the meaning of a small fun/ interesting fact)

Art theory.

It is important to explore alternative theories of art put forward by prominent theorists and philosophers of art. George Dickie was a pioneer of the idea of an institutional definition of art that had its “origins in Arthur Danto's 'Artworld'” (Lord, 1980). This theory has been thoroughly analysed by multiple sources.[1] One of the criticisms levelled against Dickie by Lord is the manner in which he used the terms ‘art institution’ and ‘art world’ interchangeably as “To do so is to prejudge the issue by assuming that the artworld is an institution[2] ” (Lord, 1980). On this note I agree with Lord, but find her criticism lacking in nuance. While true that the art world and the art institution differ, they are intrinsically linked, inseparable and unable to operate fully without the existence of the other. It would be better to classify the art world as the superset of the art institution, wherein the art institution comprises a substantial portion of said superset. Despite the criticism there are strengths in Dickies attempt to define art, especially in his efforts to include avant-garde art which were inspired by Duchamp’s Fointain, a well know example of found art and a good litmus test for any definition of art. Ultimately the downfall of Dickie’s definition of art comes from its limited nature, placing unnecessary restrictions upon the concept of art. His acceptance of convention as laid down by institution undermines the fundamental spark of invention gifted to the artistic greats, those who push the confines of what is established as convention. Dickie attempts to circumvent this caveat to his definition by claiming that as new works and practices rise to prominence, they become convention. This overlooks the time before this rise to prominence where an unknown work or practice flies under the radar. Think of how many great artists works were shunned or undiscovered while they were alive. Do we consider that Van Gogh was not an artist while still alive but became one after his death? What of the hobbyist with incredible skill? The nobody whose masterpieces will forever go undiscovered and unappreciated? Why should establishment be the gates to art? Dickie’s ambitions are virtuous, but his execution falls behind through his attempts to force a definition even he is uneasy about (Lord, 1980).

One of Plato’s philosophies is founded on the idea that art imitates the world and life. This theory has become known as ‘art is imitation’ or ‘mimesis’. Plato suggests art is a copy of the world made through the interpretive lens of the artist. Plato’s definition of art is as a fundamentally inaccurate and flawed representation of the subject portrayed, inferior to the original creations of God, which Plato considers to be perfection and further inferior to the works of craftsmen who seek to physically recreate gods’ creations (Braembussche, 2009). This separation of the medium of the craftsman and the medium of the artist into entirely different categories is fundamentally flawed, founded on a misunderstanding of the most basic creative workings and desires of both the craftsman and the artist. Of additional consideration is the artist who incorporates extensive random elements into their works, the spatter painter for one, or the autonomous sketcher for another. Where does the abstract stand within this definition? Such an important aspect of art has no place within the idea of mimesis, and therefore the idea of mimesis should hold no place within the definition of art.

While impossible to cover every past definition of art, notable attempts include art as expression of emotion; as judged by its aesthetics; as judged by formal qualities instead of its aesthetic qualities; within a social and historical context; and more. Evidenced by the lack of a unified definition of art, fair analyses could conclude that all prior definitions of art have failed to capture the concept in its entirety. While attempting the very thing countless before have failed to accomplish, I relinquish that I too, am liable to failure in such complex matters, however failure to conclude a journey does not constitute failure in all regards. Proceeding with caution and acknowledging potential failings, a definition can be attempted by heeding the lessons of past definitions, primarily their excessively restrictive nature, barring rightful holders of the title of artist from achieving their deserved accolades.

So, what is art?

Exploration of multiple methods used to define art shows limitations in all of them. Attempting to define art by its merits is only reflective of the perceived quality of the art, not its standing as art. Discrediting art based on its perceived merits opens the door to discrediting art based on bias or discrimination, instead of objective classifications. The institutions of the world exert high levels of control over the acceptance and popularity of art, and historically the definition. While the importance of the institution cannot be understated in the continuation and patronage of the arts, history shows the restrictive nature of defining art according to the opinions of an institution. Viewing art through a semantics lens produces the most volatile method of defining art. Due to the nature of neology, and the ability for a word to adapt a new meaning based on its use, the linguistic definition of art can be as changeable and fickle as humanity. Therefore, purely basing a definition of art on semantics makes empirical categorisation impossible. Art theory has historically failed in this same endeavour. However, this does not inherently mean that the effort is futile, unless you accept Ambrose Bierce’s definition of art as truth, “Art, N, This word has no definition” (Bierce, 1911), in which case attempting to define art is a futile endeavour, as time may prove it to be. Assuming the contrary, failures within art theory to define art are not due to it being an impossible task, but are caused by narrowminded approaches and understanding of what art it, causing definition attempts to be overly restrictive, creating edge cases that undermine the definition integrity.

Heeding lessons learnt from these failures, is it now possible to create a definition for art? In my opinion yes, and I propose the following definition, Art, N, The resulting work of an intentional process of creation. It is important to clarify the semantics of such a definition to dissect potential shortcomings.

Firstly, ‘intentionality’ in the creation refers not to an intentional result, but intention to create in the first place. Splatter art would be a pertinent example of this. Splatter art is random by its very nature. The technique involves relinquishing control of the result. The artist can influence the result by adjusting factors such as distance from the canvas, viscosity of the paint, shape of the brush, etc, but ultimately the artists relinquish control, and therefore an intended result. However, the artist has intended to undergo this process, and while there is no intention in the result, there is intention in the creation. This would differ from someone accidentally knocking over a glass of red wine onto a white carpet and calling it art as there is no intentionality in this act. Even similar acts where wine is spilt out of malice or anger would not qualify for the definition, as while the act is intentional, the intention is

not to create art. This does raise the question of found art; the process of finding an object, material, or scene, and declaring it to be art. This is a well-established form of art that does not involve the process of intentional creation, and consequently does not fit with my proposed definition, at least at face value. Finding an object and declaring it to be art is not creation of the object, nor is there intentionality in the finding. However, to exclude a well-established and accepted form of art from my definition is an obvious flaw, to which I propose the following reasoning. Found art is not art in of itself. Rather when an object is found and declared to be art, it is the narrative, story, representation, and/or presentation of said object that becomes art. Let us look at Fountain, by Marcel Duchamp. Fountain is a standard urinal that was found by Duchamp, which he took and elevated to the position of art. Fountain is an important and well recognised example of found art. Its example sets a precedent for the validity of found objects as art. Duchamp is quoted as saying found objects are "everyday objects raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist's act of choice" (Martin, 1999). In other words, found objects are elevated to the status of art by the artists intentional choice to create the situation in which it can be interpreted as art. This can be done through narrative, story, representation, and/or presentation, or other methods. Duchamp’s statement serves to strengthen the validity of the proposed definition, and at the very least acts as a method of confirming its compatibility with found art.

Intentionality in creation is not limited to humans. There is evidence to suggest that animals intentionally create drawings, for example fish pushing sand into shapes. While we do not know for certain if these acts are processes of creation, if that is proved, there is no reason to exclude said creations from categorisation as art. In acknowledging this, it does open the door to debate around existence and the universe being classified as art, depending on your religious beliefs. A Christian, believing the universe was intentionally created by God, would thus believe that existence itself is art. While I would agree that, should god prove to exist, existence should be classified as art, that bridge can be crossed when proof of Gods existence is found.

Distinction should be made between creation: to make an object, narrative, or work, using creativity, and production; to make something for a set purpose (besides creativity). For example, a mass-produced hammer would not qualify as art, but a bespoke, hand-crafted hammer would. The difference is nothing to do with the product, or the result, but the intention in the process of creation or production.

How then, would one define something appearing to be art, but not adhering to the proposed definition? Something that is inherently beautiful but not art? Do we also decide that something is art simply because it appears to be so? That is one possibility, and as per the rules of neology, if enough people start to refer to the object of such speculation as art, then it shall be so. However, I once again propose an alternative, that we refer to said objects as ‘artistic’, expanding upon the existing definition of the word to include the example given.

Chapter 2: Is AI Imagery Art?

What is AI? A technical breakdown.

Artificial Intelligence is the concept of computer intelligence at the point where a computer program becomes capable of sentient thought. Historically AI was purely a figment of the imagination, a flight of fantasy of a distant future. AI has been prophesized to bring onto humanity either Armageddon, a dystopia where AI turns violent and wages war with its human creators, or a utopian existence, where AI machinery is employed to free humanity from the endless slog of the 9 to 5. The term AI as we use it today is far different from truly sentient AI. So, what is AI today?

Computers run with multiple layers of abstraction, distancing the end user from the most basic workings of the hardware, microcode, instruction sets, OS, and code[3] (pp_pankaj, 2023). The typical user will operate a computer at what is known as the user level, which is completely removed from any of the inner workings of the system, using exclusively premade programs on their computer with a premade operating system, without thought given to how the computer works. To properly understand how AI works it is useful to compare it to the working of a computer. A high-level programming language allows programmers to streamline the coding process by enabling instructions and algorithms to interact to produce a desired result. Just like you manipulating equations using pen and paper to produce the solution you need.

High level languages are compiled to execute as machine code (Taviss, 2021). Requiring all the previous steps of a high level language, machine code also requires the programmer to determine how the algorithms and instructions are executed, by pointing to exact places in the computer memory (RAM) to store variables while the maths is being completed[4]. Think of this as doing the same maths equation in your head, memorising each step of the process and the result of each step as you complete it. Each step higher up the computer system hierarchy you get, the more involved and complicated it becomes. Eventually you get down to raw metal computing, where logic gates and circuits are controlled to produce the result. This would be like doing the same maths equation, but having to individually control every neuron that fires in your brain and in what order. [5]

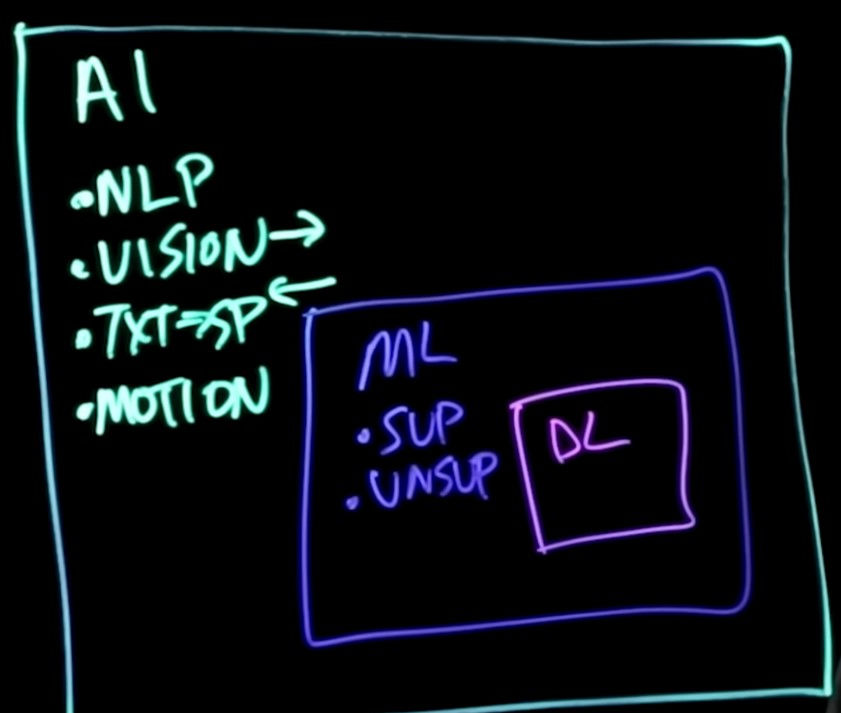

The workings of AI are like the workings of a computer. AI is comprised of several layers of technology built up to a user level program. To understand how AI works, it is important to understand the core technologies that it is built upon. These can be split into 2 separate categories, what I will refer to as the core processing category (CPC), and the interfacing and interpreting category (IIC). Both categories are individual programs working together to create the final program. IIC includes all the different technologies AI uses to interact with and understand the world it is interfacing with, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP), Machine Vision, Text to Speech, etc (IBM Technology, 2023). For example, a large language model (LLM) (Chat-GPT) must be capable of understanding human expression through text. Computers, 100% literal in their interpretations, find this difficult. Once the relevant data has been processed by the IIC, it must be passed onto the CPC, the brains of the operation, made up of what we know as Machine Learning and Deep Learning layers. The CPC is what takes the input data from the IIC and turns it into a result. Compare this to the human body. The IIC are the eyes, ears, etc, allowing you to take in data from the world around you. The CPC is the brain, processing this data and producing a result. Let’s say you are walking down the road and you see a football suddenly come flying towards your face. Your eyes (the IIC) will see the ball, and pass the information to the brain for further response. The brain (CPC) processes what the ball means, and produce an action, dodging the ball. Each of these technologies are extremely complex and most of them will involve some form of Machine Learning or Deep Learning to support their function.[6]

Machine Learning (ML) refers to a computer program that can adjust its output by adjusting its training data and context or, input parameters. Deep Learning (DL), a subsect of ML (IBM, n.d.), refers to an ML algorithm that is >= 3 neural layers deep. A neural layer is a processing step as part of a larger neural network (NN), which is composed of neural nodes, each of which processes or interoperates the input data differently. Shown right is a diagram of a DL NN, where each neural node is represented by a circle, each neural layer is represented by a column, and the NN is the whole. Arrows show all directions data can flow through this NN. NN get their name because they are intended to replicate the way in which a brain fires its neurons (IBM Data and AI Team, 2023).

While structured for specific tasks, NN require training to produce useable outputs. The following formula represents the training process.

∑wixi + bias = w1x1 + w2x2 + w3x3 + bias

output = f(x) = 1 if ∑w1x1 + b>= 0; 0 if ∑w1x1 + b < 0

(IBM, n.d.)

Weights and a bias are applied to the input of a neural node when processing an output, which is then sent to the next node to undergo the same process. Weights are used to signify the importance of the input data, which controls the strength of the influence upon the output. A bias is used to shift the resulting data from the input and weight calculations to further extremes. Simplifying the equation above we get:

(Node Input + Weights) + Bias = Node Output,

or (I+W)+B=O.

The process of tweaking the weights and bias to adjust the node output is known as training.

As the process of training a NN is largely trial and error, it is extremely time consuming. The process can be automated with ‘training data’. Upon initialisation, the weights of a NN are randomised, producing a random result. If the output differs from the training data significantly, the NN is punished, letting it know that it produced a bad result and needs to try something different. If the result is good the NN is rewarded, letting it know it should continue in the same direction. Repeated iteration allows the NN to grow, and get closer to the training data, in a process known as machine learning. If you ever use an AI program you will be given an opportunity to rate the output, allowing the AI to constantly be ‘learning’ and updating its weights to produce a better result.[7]

Is AI Imagery art?

Controversy around AI generated imagery originates from two concepts. First, AI in its current state is incapable of sentient thought. Its outputs are purely algorithmic, having more in common with a random act of nature than an act of artistic intent. Second is the use of other artists works as training data without the permission of the artists, cultivating the narrative around AI generated imagery as one of IP theft and copywrite infringement. These concepts call into question whether AI generated imagery, or AI Art as it is more commonly known, is deserving of the title of art.

A user creating an AI image enters a ‘prompt’ and awaits a response. Prompts can range from anything as simple as a single word to an in-depth description of the desired result. Upon the creation of the prompt, all control is handed over to the AI for it to interpret, and then run through the NN that make up the functioning heart of the program, which then produces the result. Through analysing this process, we can determine if AI generated imagery counts as art.

When tested against my definition, it is necessary to discern if there is intentionality, and a process of creation. When considering intentionality, there are 3 actors to consider: the AI prompt writer; AI creator/s; and artists whose work contributed to the training data. The latter are easily dismissed as they are often unaware of their artistic contributions in training or the creation of an image. The creators of the AI are likewise unaware as to the usage and outputs of their program, therefore neither party can be accredited with having intentions over the output. Equally it is not considered that Adobe is to be the artist of every work that is created using their programs, nor a paint manufacturer the artist of each painting made with their medium. Furthermore, the creators of the AI do not have input into the final functioning of the AI because of the training process where the AI is fed art to automatically adjusts its weights. Because of this the AI in effect becomes a separate entity. This leaves for consideration the AI itself and the prompt writer. As previously discussed, AI in its current state is incapable of sentient thought and, by definition, cannot be capable of having intention. Intention can be assigned to it by another, but AI itself cannot be intentional. For example, a hammer is created with the intention of driving nails, but this may not be its only use case. A hammer can be used as a weapon, a tool of destruction, a prybar, a doorstop, etc. The hammer itself does not have any intentionality within it, instead its intention is imparted upon it by its user. Finaly this leaves the prompt writer. As with the other stake holders, the prompt writer is blind to the inner workings of the AI. However, this in of itself is not a discrediting factor in lacking intentionality. In this case the opposite is true, the prompt writer does have intentionality, sometimes considerably so depending on the details contained within the prompt. There is intention in deciding which AI program to use, the desired results, the details and descriptions included in the prompt, and often stylistic expectations of the result. Not having direct control over the result cannot be equated to a lack of intentionality, after all to allow the honour of a splatter artist’s work the title of art, we cannot then claim in opposition to this that the lack of exact intention is the same as no intention.

This leaves the question, now it is understood the prompt writer does have intention in the creation of AI imagery, is the prompt writer engaging in an act of creation? Once again comparing all the stakeholders who could be said to be creating the imagery it is possible to rule out the AI’s creator and the artists who provided the training data for the same reasons as before. It cannot be ruled out that AI is creating the image however, there is little else to describe what it is doing. But does the prompt writer have any claim as to the creation of the work? In short no. There is no difference between the prompt writer going to an AI and requesting a work be created and someone commissioning an artist to produce a painting with similar instructions. The inspiration or idea may come from the prompt writer but ultimately the prompt writer is doing nothing but commission an external entity to create a work. This then means that the prompt writer cannot be said to be the creator of the work.

Under my proposed definition of art, AI generated Imagery cannot be classified as art. How then can one classify AI generated imagery? To answer this question, why not ask the AI itself? In the words of Chat GPT-4, AI “opens up a whole new realm of possibilities for artistic expression.”[8] While understanding that anything generated by AI cannot be taken as factual, or even have any basis in reality, it is fun to see that AI itself would categorise itself in a way that fits with my earlier proposed definition of ‘artistic’ as seen in chapter 1, subchapter 5. This holds true for today, but does it hold true for the future? As previously discussed, AI as it is today, also known as Artificial Narrow Intelligence, is lacking in sentient thought. What happens when AI evolves to become what is known as Artificial General Intelligence, or Artificial Super Intelligence? “Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) would perform on par with another human, while Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI)—also known as superintelligence—would surpass a human’s intelligence and ability” (IBM Data and AI Team, 2023). At this point in the development of AI, when it has reached a state of independent and sentient thought, can its creations still be considered as not art? Predicting the future is an impossibility, and so to predetermine such a statement would be a declaration of foolishness, but if AI does become sentient, should it comply with the definition of art, there is no reason for it not to be classified as such.

Consideration should be given to other definitions of art and how they intersect with AI. Returning to the subject of linguistic semantics and the concept of neology, it is clear that AI generated imagery could be considered art. AI companies coining the phrase ‘AI art’ is a clear first step in this direction, and the widespread adoption of this phrase strengthens the possibility of AI imagery being considered art. The only obstacle preventing this result is the equally widespread objection to the classification. At the present the indecision around the classification of AI imagery is too much to claim semantically that AI is art. This is a developing topic, and future developments and narratives may sway the result in either direction. Subsequently, the language by which AI generated works are described as is important, and care should be taken by those wanting to present an impartial opinion on the matter to use language that does not stand to sway public opinion and cultural development, for in doing so one may invalidate their commentary by way of insighting aforementioned change and causing AI to be semantically defined as or as not art. As it stands today, under the science of linguistics, AI cannot be defined either as art, or not art, but instead it floats in a turbulent limbo of heated arguments and fiery opinions.

Depending on your interpretation of the Institutional Theory of art, and Plato’s mimesis, AI imagery could be art. A key element in Dickie’s institutional theory of art revolves around the creation of new institutions. AI imagery has become widespread and highly adopted, being used by massive corporations for advertising, included in video games, and used by numerous ‘AI Artists”. It is without question that AI imagery has developed to the point where it could be considered an institution. AI imagery also fits exceptionally well with Plato’s definition of art, one where art imitates the world around it. AI is by its very nature an imitation, incapable of sentient thought, individual creativity, or any ability to make something that has not already been made or concepted. At face value this would make AI imagery compatible with Plato’s theory of art, however if you start to look at the origins of his theory, it becomes more contentious. Plato defines art by how many levels of imitation it sits down the ladder, away from the top rung that is pure creation by God. AI differs in this sense from traditional arts in the sense that it imitates traditional art itself, not the world around it. This would place it one rung below traditional art on the imitation ladder, resulting in a product that is lesser than art. It would be impossible to say without asking Plato himself, but this additional level of imitation would likely result in a less than gracious opinion of AI imagery.

As discussed in chapter 1 subchapter 2, merits are often used to define art by the public. There are several different merits that could be applied when an individual attempts to qualify a work as art, ranging from evaluations of the history or meaning behind the work, assessment of the technical skills required in its creation, its aesthetic qualities, and more. AI imagery however is lacking in all these merits bar one. As AI imagery is purely artificial in its creation, it has no historical context nor greater meaning inherent within it. There are no technical artistic skills in its creation, or any skills at all in the traditional sense, rather it would be more appropriate to say that AI imagery is ‘manifested’. The only merit one could assign to AI imagery is its aesthetic quality, and while true that AI imagery is often beautiful, it is rare for one to evaluate a work based purely on its aesthetic qualities. This is evidenced by well established artists and their copycats. An original work by the likes of Picasso is often adored and admired, while a near identical copy made by a skilled fraudster is looked down upon and disregarded. The skills required to make the copy are the same, as is the aesthetic quality, but other elements reduce its value to nothing. It is hard to see how anyone would consider AI imagery to be art when they evaluate art by its merits.

Chapter 3: Conclusion.

Having explored several theories of art, and possible ways of defining art, there are multiple potential answers that could be considered when answering the question of whether AI generated imagery is art. On examination past methods of defining art all appear to have critical faults that have prevented them from gaining widespread acceptance therefore usage of these prior methods of defining art is unlikely to provide sound reasoning for any conclusion drawn. Knowing this I attempted to create my own personal definition of art, by taking into consideration the failing of past definitions. As previously discussed, it is unlikely that I would have succeeded where so many other incredibly smart individuals have failed, however lacking any solid bases by which to attempt to answer the question set forth, I must resign myself to failure in answering the question or attempt to build the foundations myself. It is because of this I draw my conclusion based on my personal definition of art.

As a reminder of my definition;

Art, N, The resulting work of an intentional process of creation.

Because there is no one entity or person that can be said to have both created the work and had intention to create the work AI generated imagery as is cannot be said to be art. This does not preclude it from having ‘artistic’ qualities, being something of beauty, or worthy of admiration. Because AI generated imagery is not art, the matter of its creator is not something I have discussed here, due to the causality clause within the original question set out at the start of this discussion. AI generated imagery not classifying as art is not mutually exclusive with not having a creator. Further thought could be given to the identity of the creator of AI generated imagery. This is a very important matter in determining factors such as copywrite holders of AI generated imagery. As it currently stands AI generated works cannot be assigned copywrite, both in the US (STEPHEN THALER, Plaintiff, v. SHIRA PERLMUTTER, Register of Copyrights and Director of the United States Copyright Office, et al., 2023), and in the wider world generally as represented in multiple examples of case law globally. Further discussion could be aimed at determining how other areas of AI creation should be classified, such as music, animation, 3d modelling, writing, etc.

Technology is always changing and evolving, and law always seems to be lagging behind. The EU is currently introducing swathes of much needed legislation designed to reduce and prevent the disgraceful anti-consumer practices often employed by big tech. While the EU should be praised for its efforts, it comes years too late, and it is notable that they are the FIRST, not the last to implement these much-needed laws at large scale. It is thus important to start having the discussion today as to the future of AI, when it does become sentient, and how we should treat it then. Matters of copywrite will need to be re-evaluated, its ability to create art will likely change, and its capabilities will expand. As important as it is today, it will become increasingly important with the development of AI to consider the morals of using AI and create pre-emptive global legislation surrounding its use and creation.

[1] It is worth reading George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, An Institutional Analysis by Haig Khatchandourian and Convention and Dickie's Institutional Theory of Art by Catherine Lord for a proper analysis of the theory and academic critique of its content.

[2] Of note is the difference in definition in the manner Dickie and Lord use the term Institution to how I use it in subchapter 2. Lord’s critique should be read for further understanding on the matter.

[3] Code can be further split into high level languages and machine code/ assembly code.

[4] Assembly code is more complex than this and works by creating a set of instructions for a computer to follow in a set order based on the desired results of the program. The instructions used are dependent on the instruction set of the computer being used, for example the x86 instruction set used by most Windows and Linux computers today.

[5] This is an oversimplification of how a computer system works and should not be taken as pure fact. Instead, it is intended to generally educate and give an idea of how a computer system works. Please see the reading list for additional information to aid understanding.

[6] This is another oversimplification of how AI works. Please consult the reading list for further information.

[7] In reality the process of creating and training an AI is considerably more complex and involves lots more maths than covered here, but this overview should allow a basic understanding of how AI and NN work and subsequently where the controversy around AI comes from.

[8] Quote generated and pulled from Chat GPT-4, and AI large language model.

Illustrations List

Bibliography

712, A., 2024. Olimpia. [Online] Available at: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/olympia-712[Accessed 28 01 2024].

ALinguisticsPerson, 2024. Lexical semantics. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexical_semantics[Accessed 01 2024].

Anon., 2022. The Essence and Significance of Art. [Online] Available at: https://www.eden-gallery.com/news/why-is-art-important[Accessed 01 2024].

Anon, 2024. Neologism. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neologism#:~:text=Most%20definitively%2C%20a%20word%20can,meanings%20into%20a%20language's%20lexicon.[Accessed 26 01 2024].

Béhague, G., 2006. Diversity and the Arts: Issues and Strategies. Latin American Music Review, 27(1), pp. 19-27.

Bierce, A., 1911. The Devil's Dictionary. s.l.:s.n.

Bodle, A., 2016. How new words are born. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/mind-your-language/2016/feb/04/english-neologisms-new-words[Accessed 01 2024].

Braembussche, A. v. d., 2009. Thinking Art. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bystryn, M., 1978. Art Galleries as Gatekeepers: The Case of the Abstract Expressionists. Social Reserch, 45(2), pp. 390-408.

David S Cooper, E., 1999. THEORIES OF ART- RONALD W. HEPBURN. [Online] Available at: https://users.rowan.edu/~clowney/Aesthetics/theories_of_art.htm[Accessed 01 2024].

Duchamp, M., 1917. Fountain. [Art].

Freeland, C. A., 2001. But is it art? : an introduction to art theory. 1 ed. Oxford(New York): Oxford University Press.

Howarth, S., 2000. Yves Klein IKB 79. [Online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/klein-ikb-79-t01513[Accessed 25 01 2024].

IBM Data and AI Team, 2023. AI vs. Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning vs. Neural Networks: What’s the difference?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/blog/ai-vs-machine-learning-vs-deep-learning-vs-neural-networks/[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM Technology, 2023. AI vs Machine Learning. [Online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RixMPF4xis[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM, n.d. What is a neural network?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/topics/neural-networks[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM, n.d. What is deep learning?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/topics/deep-learning[Accessed 01 2024].

Jamot, P., 1927. Manet and the Olympia. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 1, 50(286), pp. 27-35.

Jason Rosenfeld, P., 2004. The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century. [Online] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sara/hd_sara.htm[Accessed 27 01 2024].

Khatchadourian, H., 1979. George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, An Institutional Analysis.. Nous, 13(1), pp. 113-117.

Klein, Y., 1959. IKB 79. [Art].

Lord, C., 1980. Convention and Dickie's Institutional Theory of Art. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 20(4), pp. 322-328.

Manet, E., 1863. Olympia. [Art].

Martin, T., 1999. Essential Surrealists. bath: Dempsey Parr.

Murakami, T., 2020. Friendship Forever. [Art].

NapoliRoma, 2024. Neologism. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neologism[Accessed 01 2024].

pp_pankaj, 2023. Computer System Level Hierarchy. [Online] Available at: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-system-level-hierarchy/[Accessed 01 2024].

pp_pankaj, 2023. Computer System Level Hierarchy. [Online] Available at: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-system-level-hierarchy/[Accessed 01 2024].

Schuh, A., 2017. Queer Representation and Inclusion within U.S. Museums , Oregon: University of Oregon .

Stanislavivana, B. K., 2023. Science in the Environment of Rapid Changes. Brussels, InterConf Scientific Publishing Center.

STEPHEN THALER, Plaintiff, v. SHIRA PERLMUTTER, Register of Copyrights and Director of the United States Copyright Office, et al. (2023).

Taviss, S., 2021. Asm2Seq: Explainable Assembly Code Functional Summary Generation, Kingston, Ontario: Queens University.

Vecelli, T., 1534. Venus of Urbino. [Art].

Whiteley, T., 2020. What is the Purpose of Art?. [Online] Available at: https://peninsulaartssociety.org.au/what-is-the-purpose-of-art/#:~:text=Art%20can%20uplift%2C%20provoke%2C%20soothe,picture%20of%20the%20human%20condition.[Accessed 01 2024].

Reading List

712, A., 2024. Olympia. [Online] Available at: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/olympia-712[Accessed 28 01 2024].

ALinguisticsPerson, 2024. Lexical semantics. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexical_semantics[Accessed 01 2024].

Anon., 2022. The Essence and Significance of Art. [Online] Available at: https://www.eden-gallery.com/news/why-is-art-important[Accessed 01 2024].

Anon, 2024. Neologism. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neologism#:~:text=Most%20definitively%2C%20a%20word%20can,meanings%20into%20a%20language's%20lexicon.[Accessed 26 01 2024].

Béhague, G., 2006. Diversity and the Arts: Issues and Strategies. Latin American Music Review, 27(1), pp. 19-27.

Bierce, A., 1911. The Devil's Dictionary. s.l.:s.n.

Bodle, A., 2016. How new words are born. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/mind-your-language/2016/feb/04/english-neologisms-new-words[Accessed 01 2024].

Braembussche, A. v. d., 2009. Thinking Art. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bystryn, M., 1978. Art Galleries as Gatekeepers: The Case of the Abstract Expressionists. Social Reserch, 45(2), pp. 390-408.

David S Cooper, E., 1999. THEORIES OF ART- RONALD W. HEPBURN. [Online] Available at: https://users.rowan.edu/~clowney/Aesthetics/theories_of_art.htm[Accessed 01 2024].

Duchamp, M., 1917. Fountain. [Art].

Freeland, C. A., 2001. But is it art? : an introduction to art theory. 1 ed. Oxford(New York): Oxford University Press.

Howarth, S., 2000. Yves Klein IKB 79. [Online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/klein-ikb-79-t01513[Accessed 25 01 2024].

IBM Data and AI Team, 2023. AI vs. Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning vs. Neural Networks: What’s the difference?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/blog/ai-vs-machine-learning-vs-deep-learning-vs-neural-networks/[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM Technology, 2023. AI vs Machine Learning. [Online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RixMPF4xis[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM, n.d. What is a neural network?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/topics/neural-networks[Accessed 01 2024].

IBM, n.d. What is deep learning?. [Online] Available at: https://www.ibm.com/topics/deep-learning[Accessed 01 2024].

Jamot, P., 1927. Manet and the Olympia. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 1, 50(286), pp. 27-35.

Jason Rosenfeld, P., 2004. The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century. [Online] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sara/hd_sara.htm[Accessed 27 01 2024].

Khatchadourian, H., 1979. George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic, An Institutional Analysis.. Nous, 13(1), pp. 113-117.

Klein, Y., 1959. IKB 79. [Art].

Lord, C., 1980. Convention and Dickie's Institutional Theory of Art. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 20(4), pp. 322-328.

Manet, E., 1863. Olimpia. [Art].

Martin, T., 1999. Essential Surrealists. bath: Dempsey Parr.

Murakami, T., 2020. Friendship Forever. [Art].

NapoliRoma, 2024. Neologism. [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neologism[Accessed 01 2024].

pp_pankaj, 2023. Computer System Level Hierarchy. [Online] Available at: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-system-level-hierarchy/[Accessed 01 2024].

pp_pankaj, 2023. Computer System Level Hierarchy. [Online] Available at: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-system-level-hierarchy/[Accessed 01 2024].

Schuh, A., 2017. Queer Representation and Inclusion within U.S. Museums , Oregon: University of Oregon .

Stanislavivana, B. K., 2023. Science in the Environment of Rapid Changes. Brussels, InterConf Scientific Publishing Center.

STEPHEN THALER, Plaintiff, v. SHIRA PERLMUTTER, Register of Copyrights and Director of the United States Copyright Office, et al. (2023).

Taviss, S., 2021. Asm2Seq: Explainable Assembly Code Functional Summary Generation, Kingston, Ontario: Queens University.

Vecelli, T., 1534. Venus of Urbino. [Art].

Whiteley, T., 2020. What is the Purpose of Art?. [Online] Available at: https://peninsulaartssociety.org.au/what-is-the-purpose-of-art/#:~:text=Art%20can%20uplift%2C%20provoke%2C%20soothe,picture%20of%20the%20human%20condition.[Accessed 01 2024].

Comments